Do I mean best or favourite? Since art is entirely subjective and there can be no objective measure of success outside of the financial, obviously I mean best.

The two pieces of 2017 art that moved me the most were the new series of Twin Peaks, and the album Whiteout Conditions by The New Pornographers. But some of the movies were pretty good too. I dug Logan, Lucky and Logan Lucky. I enjoyed Wonder Women, Wonderstruck and Wonder Wheel, but missed Wonder and Professor Marston and the Wonder Women. I saw Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge and Alice Lowe’s Prevenge. I enjoyed Gerald’s Game, and waited for Molly’s Game. I started the year with1994’s Ladybird Ladybird and ended it with 2017’s Lady Bird. It’s important to maintain variety.

My approach to release dates is haphazard and designed to annoy. There are some 2016 films that were not released in Australia until 2017. There are some 2017 films that won’t be released in Australia until 2018. And there are some 1992 films that trump everything released this year because nobody’s figured out how to make a film better than Sneakers.

Also, I do a film podcast. It’s good. You should listen.

All right. On with it. From my arbitrarily-numbered yet mandatorily-divisible-by-five list of favourite films, it hurt to cut: Moonlight, 20th Century Women, Prevenge, Colossal.

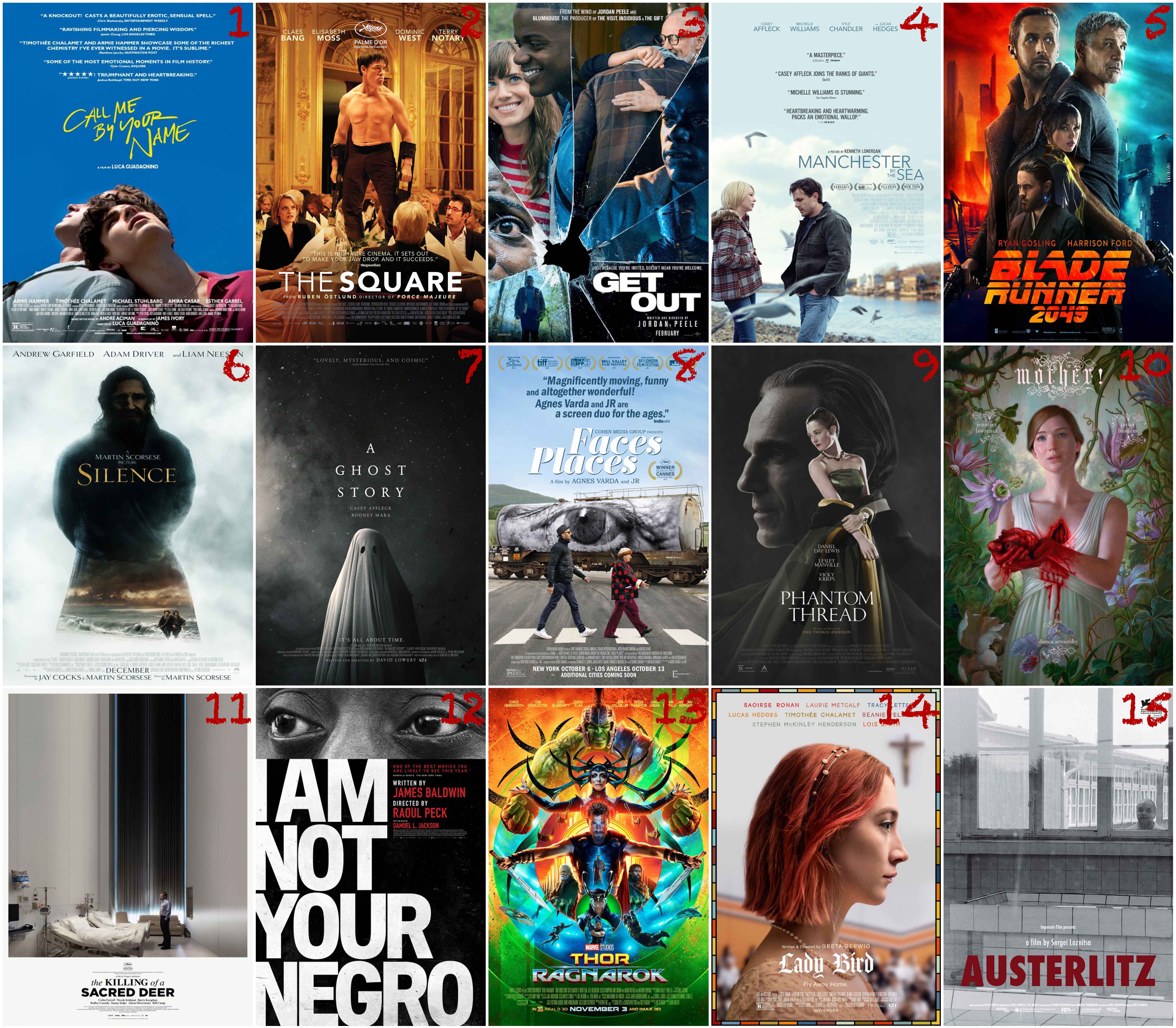

15. AUSTERLITZ

These lists are always best when they’re composed by my subconscious; the overly considered lists are too self-aware and compel me to second-guess myself, as I err toward critical consensus or provocative contrarianism. They’re too calculated. So I let my feelings do the selecting, and was surprised to discover this film made it onto my list. Austerlitz is a documentary that unobtrusively surveils tourists as they wander about the site of a former concentration camp, listening to tour guides, munching on food, taking selfies, barely present. The weight of the history around them barely registers as they dutifully glance at each building and point of interest, as if clinically ticking off a mandated checklist. Teens walk through the former camp adorned with ironic t-shirts: “Fuck happiness!” “Cool story, bro!” The latter, a cheap t-shirt designed to cash in on a meme, becomes, in the context of this film, an unwitting symbol for Holocaust denial, unbeknownst to the kid wearing it. The accidental details forged through observation. In Austerlitz, and in Austerlitz, modern culture invades and tapes over the past even as it tries to honour it. The rare moment where someone appears to be in the midst of an affecting experience is offset by the figure in the background with a selfie stick. It’s an ugly indictment on us, that even those willing to make the effort to engage with one of living history’s worst moments can’t do so without becoming grotesque. In the notes I made after seeing the film, I described it as “imperfect”, and lamented the way the careless ADR lip-syncing of the tour guides – presumably required for either technical or legal reasons – undercuts the reality of the film. The observational style of Austerlitz also apes the narration-free vignette approach that director Sergei Loznitsa applied to his haunting and flawless 2014 documentary Maidan, and what felt fresh and dangerous then feels familiar and habitual now that it’s been done twice. And yet, I was crushed, emotionally and spiritually, when I left the cinema, and had to walk around the city to shake off what I’d just experienced. The walk did not work: five months later I can’t stop thinking about this flawed and outstanding film. The subconscious wins out.

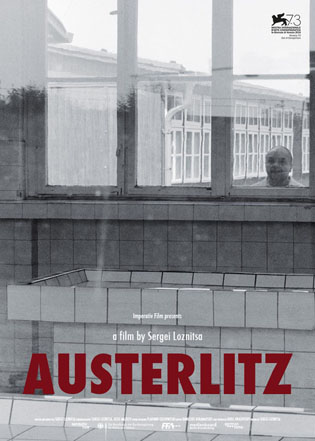

14. LADY BIRD

14. LADY BIRD

My love-hate relationship with Noah Baumbach’s films lurched firmly into love when Greta Gerwig became his collaborator: as star, as muse, and most importantly as screenwriter, Gerwig’s contribution appeared – from the outside, at least – to help push Baumbach’s works into a new class, with 2012’s Frances Ha and 2015’s Mistress America both perfectly-executed chronicles of the modern millennial. It’s no surprise that Gerwig’s directorial debut should be so assured and so confident. Somewhat reductively, it’s a Rushmore for our times – even contemporaneous with that film given it’s technically a period piece – a coming-of-age story where overcoming pretention and forced mannerisms is as important to growth as learning self-confidence and kindness. Pretention is shown to be not a way of life, but a mere placeholder until these kids can figure out who they really are; never has the transient nature of teenage identity been so keenly depicted. Saoirse Ronan is note-perfect as Lady Bird, shifting from heartbreaking vulnerability to acerbic comedy without even a blink of the eye. Lady Bird is not overburdened with ambition, which is not a bad thing for a story such as this. It hits all the bullseyes it aims for, with each and every scene ringing true, and beautiful side-moments with seemingly inconsequential characters adding to both the world and the theme.

13. THOR: RAGNAROK

No single film has made me question the conventions of genre as forcefully as Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarok. It is not merely a funny film, but a full-on, actual comedy, one you could justify shelving in the comedy section of the video store. Genre labels are redundant, sure, but so are video stores, and so the analogy holds. The Marvel Studios films have been praised and criticised in equal measure for their persistent quippery, but Ragnarok ventures further than that, painting a world in which the comedy is situational and not just reactive. Nearly everything in this film is played specifically for laughs, which does diminish the stakes somewhat: its breakneck pace leaves little room for the drama to properly land. Key characters are dispatched with little thought, and momentous plot developments are delivered in single, throwaway lines. But whereas I found a film like Spider-man: Homecoming to be more successful at balancing all its elements, it did not sear itself into the brain – both my own as well as the collective throbbing mass of pop culture – the way that Ragnarok did. Iconic characters, unforgettable visuals, quotable lines, and a plot that boldly skewers colonial myths… there’s not a scene in this film that did not imprint itself permanently after a single, solitary viewing. In an age where all pop culture moves at lightning speed and few works stick around long enough to make an impact before they’re replaced with the next thing, the fact that a film such as this one can be so instantly and deservedly iconic is worthy of celebration.

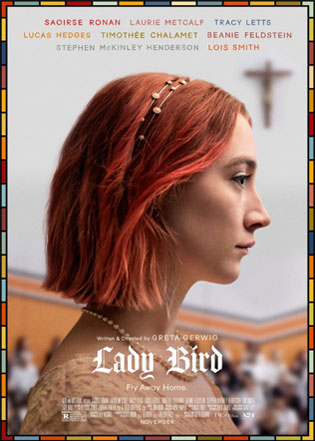

12. I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO

12. I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO

When a film carries a weight of import outside its value as entertainment, it feels slightly churlish to reduce it to its aesthetics, but not so churlish that I won’t do it anyway. Every year I hope for a documentary about a writer of impact, both artistically and politically, a film in which stock footage is laid under a vocal performance of the author’s prose, rendered by some great and richly-timbred actor. These are the sorts of film I fall comfortably into, and this is exactly what I Am Not Your Negro is: a film about James Baldwin’s life, about America then and America now, using Baldwin’s unfinished novel Remember This House as a launching point. But while the style is comfortable, the subject matter is anything but, and this should create a discord. It is searing and potent, worryingly relevant, and relentlessly perceptive. Baldwin’s writing is propulsive and beautiful, and it’s strange to hear him grapple forcefully with necessarily difficult subjects even as I’m seduced by the poetry of the delivery method. It is the mark of a great writer, and a great film, that we should be so entertained without ever losing sight of the horror that undergirds the film’s thesis.

11. THE KILLING OF A SACRED DEER

11. THE KILLING OF A SACRED DEER

All films should be judged by their own ambition: the work itself establishes the rules and then tries to follow or break them. I Am Not Your Negro is not, for instance, the funniest comic book movie of the year, but nor is Thor: Ragnarok the best documentary about modern American race relations. And so I struggled, on first viewing with what to make of The Killing of a Sacred Deer, which seemed at first to obscure its intention. Like so many of Yorgos Lanthimos’s films, the first half is so bone-splittingly perfect, that the second’s sharp veer into mere greatness – venturing into places most good films could only dream of – feels like an ever-so-slight letdown. But Killing nevertheless stayed with me, its images and ideas haunting me for months afterwards. Colin Farrell plays his spiritless heart surgeon as a man who doesn’t quite know how to act like a human being, and Nicole Kidman channels her Eyes Wide Shut energy into a perfectly-understated performance that makes this entire exercise feel much like a spiritual sequel to Kubrick’s final work. An adaptation of the Euripides play Iphigenia at Aulis, it weaves the supernatural into the modern with a tone that is always unsettling, but never illogical. The whims of the gods, the mystical aspect of vengeance, are folded into this familiar modern world as if we were still psychologically rooted in Ancient Greece. There is a tragic curse, a terrifying bargain, a devastating ending. The terms of the curse were clear from the beginning, even if Farrell’s surgeon wasn’t listening. Maybe the terms of the film’s ambition were also clear, and it took me slightly longer to accept them.

10. MOTHER!

From Bong Joon-ho to Andy Muschietti to Albert Brooks to Xavier Dolan, I suspect that the secret to making a film I connect with is to ensure its title is a simple, one-word variation on the word “mother”. Beyond the titular totem, Darren Aronofsky digs deeper. Mother! is an overt Biblical allegory that proudly eschews any sort of recognisable reality, taking place in a single location with the outside world either an illusion or an unknowable mystery. Aronofsky’s Talmudic approach to religion has informed his films Pi and Noah, so when Mother! ventures boldly into the New Testament, it’s no longer an introspective criticism from a profoundly Jewish director. To dismiss auteurism is to ignore these layers, people. Because nobody else could possibly make this film, in this way, to this effect.

9. PHANTOM THREAD

When artists make films about artists, they too often portray them as misunderstood geniuses, whose personal torment and torturous indulgences are the price we may for their great works. Paul Thomas Anderson is far too self-aware for that, and he could not have picked a more perfect moment in his filmography to make this film. Well into the second phase of his career, his films are now rightly greeted as the future classics that they will doubtless become: There Will Be Blood, The Master and Inherent Vice are the sort of works that a filmmaker would be lucky to make once in their career, and Anderson produces them with the apparent effort of a mechanised construction line. He is caught in a moment in which the release of a technically-perfect and complex film about the nucleus of human nature is something we almost take for granted, a fault that lies entirely within us, or if none of this applies to you, in me. I’m not too proud to admit it. There was no better moment for him to tell a story that dismantles the concept of The Great Maker, a self-effacing portrait that thumbs its nose at any mythology that justifies poor behaviour with artistic output. And yet, this is an obvious reading, an immediate reaction that is yet to settle only weeks after seeing the film. Because this film, as beautiful and inscrutable as any one of Reynolds Woodcock’s garments, is clearly hiding something under the surface. Whatever phantom threads Anderson has woven into the fabric of this outstanding film, they may take years to find.

8. FACES PLACES

There is a pure unfiltered joy to the films of Agnès Varda, particularly the documentaries in which she features as a key player. Faces Places is built on such a simple concept, almost too slight for a feature documentary: Varda and mural artist JR go on a road trip across rural France to take photographs of the people they meet, and paste the pictures over local structures. That’s pretty much it. But the glory of the film comes in act of celebrating those who are rarely celebrated, the people we would pejoratively but unavoidably describe as “everyday”. We are treated to the incredible stories of life in these small towns, and see the storytellers turned from humans to icons before our eyes and theirs. “Why don’t we celebrate teachers and nurses?” is a familiar catchcry in response to the ongoing worship of the farcical and talentless, and here Varda answers. From the opening Rashomon-esque meet-cute in which she speculates about how her 89-year-old self and 35-year-old JR may have first hooked up, to their wonderful affectionate banter, it is impossible not to be thoroughly charmed by this unlikely buddy comedy. But JR may be too young to properly appreciate the past, and the past is the very thing that they’ve set out to find. It’s what Varda has, in many ways, been searching for in all her 21st century documentaries, as she stops to recall her own works and life, her late husband Jacques Demy, her collaborations with Jacques Rivette. It’s more than an indulgence, as the ghosts of the past are precisely what informs this film. In a particularly moving finale, she attempts to call on her old friend Jean-Luc Godard, and discovers that she quite literally cannot revisit the past. It is gone forever. It provides a sour note that turns sweet, as she is saved by the present, a moment that provides JR with a relevancy beyond his art. The things from the past are not always worth resurrecting, and it’s often better to remember them as they are. A theme that we in this list are not yet done with.

7. A GHOST STORY

In a typical ghost story, the sporadic appearance of the spectre feels mysterious and enigmatic. But from the ghost’s perspective, it is the sporadic appearance of reality that makes him feel haunted by the real world. The living world comes at him in phases, unexpectedly, appearing and disappearing with eerie inconsistency. In this approach the film is atypical, and yet it counters with the inspired overly-typical simplicity of depicting the ghost as a figure in a sheet, presented with no self-consciousness or hint of parody whatsoever. Because it should be so overtly silly, yet it is anything but. A Ghost Story is a tonal masterpiece, a direct descendant of the displaced time-and-space surreality from the third act of Kubrick’s 2001. It is a film of time and perception, and a work of understated genius.

6. SILENCE

It felt like I was waiting a decade for this film, and that last gentle push that nudged its Australian release date into January meant that its foretold (but hardly inevitable) place in my end-of-year list would be delayed by another full calendar year. Silence is, in every possible way, all about waiting. Scorsese’s well-documented love of mid-century Japanese and Italian cinema channels itself into a stunning tale of 17th century Jesuit priests persecuted for their beliefs in Edo period Japan. One of the film’s earliest shots even feels like it’s ripped straight out of Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams, a film in which Scorsese himself performed, evoking authenticity from cinematic history and actual history in even measure. Long, languid takes combined with Thelma Schoonmaker’s perfectly idiosyncratic editing style makes this a triumph of form. But what sets it apart, what makes this a story worth telling instead of simply an indulgence in interests thematic and cosmetic, is that its Rorschachian examination of faith and religion remains entirely relevant in this moment. Silence is an argument for faith, against faith, for religion, against religion, for plurality, against fascism, without becoming either didactic or conciliatory. All ideas are challenged, and the nature of belief is explored in a way that no one but Scorsese – the Catholic filmmaker who helped forge the hedonistic excesses of New Hollywood, and who once made the most controversial but fundamentally reverential film about Jesus Christ – ever could.

5. BLADE RUNNER 2049

It is a seemingly-impossible feat to make a sequel to a film that is so beloved and so canonised and so stamped upon the minds of its admirers. A thin, barely-visible tightrope hovers over two different yet equally-treacherous perils: on one side, you risk missing the point of the original and creating a follow-up whose character, plot, and theme barely resembles its source; on the other, you simply retread the familiar beats of the previous work, applying a fresh coat of paint to the old structure. In theory, we know that it must be possible to avoid both dangers, but how do you do this in practice? In the futuristic world of the Tyrell Corporation and blade runners and off-world colonies, in which many, many narratives are possible, do you tell another procedural about a cop hunting down rogue replicants? If you don’t, if you choose another path, have you already strayed too far from the foundations of the original that you’ve lost half the audience before you’ve even begun? Denis Villeneuve took on this unenviable task, and I am in awe that he not only beat the modern Hollywood franchise iteration of the trolley problem, but managed to create a work of art that will endure in much the same way as its predecessor. One more tortured metaphor before I moved on: it’s as if Villeneuve flipped a coin, the coin landed on its side, and was, in its final repose, a work of staggering artistic beauty. What an accomplishment. Aesthetically, the film is one of the most extraordinary examples of cinematography we have ever seen, which is really just another way of saying “shot by Roger Deakins”. Narratively, Blade Runner 2049 persistently remains a step ahead of the audience, anticipating seductive yet clumsy twists and navigating around them, telling a tale that is surprising but inevitable. Surprising but inevitable is my favourite form of storytelling, and the one I aspire to. This is also a film with something to say, examining what it means to have a distinct but advanced class system, a culture that still relies on slavery and subjugation to function. It touches on the same themes as the original, but launches into a more detailed and evolved examination. As a standalone work, it is one of the best films of the year. As a sequel to a confirmed classic, it is the new gold standard.

4. MANCHESTER BY THE SEA

I was terrified of this film. For so long. The terror began as anticipation, thanks to the fact that Ken Lonergan’s Margaret is one of my favourite films of all time, a drama with few peers that hit a high note on first impression and sustained it for six years. Few things in real life have sustained the way that film has. The constant presence of Manchester, in the background, in theory, as critical darling, as awards contender, turned my anticipation into fear so gradually that I didn’t notice until the opportunity to see the damn thing finally presented itself. It was not a case of tainted expectations, as the plaudits and praise were all noise, neither enhancing or diminishing my expectations. But the reality of this film’s existence grew every day, and I went out of my way to avoid it. It’s so easy not to see a film. You rarely have to be an active participant in your ignorance. But this time I chose participation. Because Margaret destroyed me, back in an old and barely-recognisable life, and I was afraid of what Manchester would do to me in this one. So I avoided it. As 2017 waned, the films I watched carried with them an expectation. I am a list-maker, and a categoriser, and a lover of structure, and my best of the year list, this list, cast a long and absurd shadow, and the judgement of whether a film will be worthy of a last-minute inclusion ticks over every second, growing louder as December arrives, poking at me like Poe’s telltale heart. At the beginning of the year, these films are unburdened, but here at the end it’s as if they’ve been automatically waved through into Certified Greatness by virtue of being beloved by all, and you have to make an active decision on whether to not include them, but exclude them. Under these circumstances, it is simply impossible to honestly enjoy the film in front of you. So I made another conscious decision. I decided I would definitely watch Manchester, but not until 2018, so I could view it free of those self-imposed chains. The very moment I voiced that sentiment to a friend, two days before Christmas, the chains slipped away, like Marley’s ghost suddenly freed, and I did what I thought I would not do: I sought it out. Immediately. Without hesitation. I devoured it. I loved it. The film was all new and familiar at once. Those Lonergan trademarks, once Margaret trademarks, now a signature: the protagonist’s desire for a passive authority to behave in a way that we expect; inconsistent perceptions of self reflected not through the monologue or introspection, but through competing relationships; the hand of fate, hanging over unprepared and unremarkable figures, like they’ve wandered unknowingly into Greek tragedy. A protagonist who shared with me a name, and other features I won’t name, as if general empathy wasn’t enough. What a cruel trick. Back in February, the name “Michelle Williams” was read out at the Oscars, followed by a clip: she’s crying but I am dispassionate, watching the announcement in insolation where the emotion is inferred but never felt. Ten months later, longer that it takes to create a person, the clip is in exact facsimile, only now with a new and proper context, the golden bumper graphics and parenthetical applause removed, every line the same, razing me in the exact way I’d feared, in the precise way Margaret once had. In the intervening years, I’d wondered, more than once, if my passion for this medium was on the decline. But the fear I felt at the film’s possibility, and the fact that those fears were entirely and thoroughly correct, proves to me that the passion must remain.

3. GET OUT

There are filmmakers who are masterful DJs, remixing the cinema that influenced them, creating modern versions that, at their best, are far superior than the films that inspired them. Nostalgia in its most constructive form. But few manage to do this well, and fewer manage to do this at the same time as they craft a story of supreme urgency and currency. But even fewer are Jordan Peele. Get Out riffs effortlessly on horror tropes, boasting an aesthetic that is somehow classical and subversive all at once, and Peele directs with the unfakeable energy of someone burning up with something to say. It is the logical extension of his work as co-creator and co-performer on Key and Peele, probably the greatest and most consistently high-quality sketch show in living memory, in which genre conventions are skewered and turned inside out. Once for comic effect, now, with slight adjustment, for horrific effect. It is the best horror film of 2017. It is the most 2017 film of 2017.

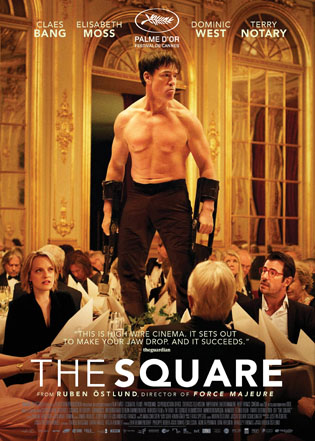

2. THE SQUARE

There are not many filmmakers who explore and mercilessly dismantle modern philosophical issues the way that Ruben Östlund does. In his satire The Square, the curator of an art museum attempts to gin up publicity by creating a literal, physical safe space just outside the building. It is pretentious and cynical move, reflected in all the film’s characters who seek out their own safe spaces and simultaneously fail to provide them for anyone they encounter. These spaces appear when least expected, in stairwells, in doorways, peppered unpredictably throughout Stockholm. They disappear when normal rules of behaviour are seemingly outranked by the rule of art, artificially imposed over societal norms. To say more would be to ruin the many glorious surprises. This is a film about how trust operates, and it is uncomfortable, unpredictable, and relentlessly funny. The Square has the aura of a meandering shaggy dog story, but there is no moment that is not carefully placed, that isn’t entirely on point. Like Östlund’s Force Majeure, it pushes past several natural endings until it discovers the ideal end note, its perfect final moments underscoring the point of this wonderful whole exercise.

1. CALL ME BY YOUR NAME

Love lies in the long grass. In Luca Guadagnino’s I Am Love, Tilda Swinton’s Emma and Edoardo Gabbriellini’s Antonio make love in a field in northern Italy, modestly shielded by the tall yellow stalks. At least, that’s how I remember it. When I spoke to director Luca Guadagnino in August, I reminded him of that same film’s visual callback to Hitchcock’s Vertigo, the push-in on a spiral of pinned hair by an unseen observer. Luca said that this was a frivolous reference, and that he would not make such an allusion if he was directing the film today. Even as recently as 2009, art was something we remembered as much as we experienced, and such a moment was designed to evoke something from a shared cultural memory. Nowadays, he said, in the era of Instagram, this shot can be immediately compared to its progenitor. The comparison is literal, not emotional, and he suggests we have lost something as a result. I tend to agree. And so I am describing the scene between Emma and Antonio based an eight-year-old remembrance, of what I think was sunlight-smeared close-ups and obscured glimpses and the sound of crickets stridulating instead of a nondiegetic score. My DVD is in the next room and it would take only a moment to confirm or refute this impression, but I’d rather pay tribute both to and with my recollection. Call Me By Your Name is a memory. The final part of Guadagnino’s “desire trilogy” that began with 2009’s I Am Love and continued with 2015’s A Bigger Splash is a Summer romance that is experienced and remembered. Throughout the film, I suspected we were not witnessing the literal unfolding of the romance, but Elio’s memory of it, long after the fact. It plays like a memory, or maybe it’s just how I’m remembering it. The memory lies, and that’s part of its charm. But it’s true that this film is so beautiful, and so funny, and so very real, with drama borne of desire instead of manufactured conflict. That not even the most desirous of dramatic friction – the perennial trope of disapproving parents – should be deployed is a testimony to the film’s earned confidence in the beauty and allure of this love story. The film’s iconic peaches, now in danger of being stripped of meaning as they are memed into parody by well-meaning fans (myself included), are a detail of memory, but also a gloriously unabashed metaphor for burgeoning love, played with in text and subtext, teased wistfully. The peaches ripen. The crickets stridulate. Elio and Oliver fall in love in a field in northern Italy. Love lies in the long grass.

New Release Films Seen in 2017:

Split, Silence, Hidden Figures, T2: Trainspotting, Kong: Skull Island, The Lego Batman Movie, Logan, A Cure For Wellness, Beaches, Life, Get Out, Tickling Giants, Guardians of the Galaxy vol. 2, Rules Don’t Apply, Free Fire, Alien: Covenant, Mindhorn, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales, Wonder Woman, The Mummy, Trench, War Machine, Transformers: The Last Knight, Baby Driver, Spider-man: Homecoming, The Beguiled, Dunkirk, War For the Planet of the Apes, The Big Sick, Mean Dreams, PACMen, Mountain, Watch the Sunset, Valerian and the City of a thousand Planets, Jungle, Call Me By Your Name, 78/52, Guardians of the Strait, Final Portrait, Tragedy Girls, Australia Day, Faces Place, Song To Song, Chasing Trane, Lucky, Manifesto, Killing Ground, Loving Vincent, Let Sunshine In, Brigsby Bear, The Killing of a Sacred Deer, Hostages, Voyage of Time (IMAX Edit), The Belko Experiment, Glory, Winnie, The Square, Rey, The Documentary of Dr G Yunupingu’s Life, Wonderstruck, Austerlitz, Beatriz At Dinner, Logan Lucky, It, mother!, The Line, Kingsman: The Golden Circle, Anthropoid, The Bad Batch, It’s Only the End of the World, Blade Runner 2049, Gerald’s Game, Detroit, Thor: Ragnarok, Spielberg, Suburbicon, Murder on the Orient Express, Justice League, Shot Caller, Downsizing, Coco, Revenge, The Disaster Artist, Pitch Perfect 3, Wonder Wheel, Nocturama, Lady Bird, Raw, The Florida Project, Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond, A Ghost Story, Voyeur, The Lost City of Z, 20th Century Women, Colossal, Phantom Thread, Star Wars – Episode VIII: The Last Jedi, Okja, The Post, Mudbound, The Babysitter, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing Missouri, All the Money in the World, I Am Not Your Negro, A Man Called Ove, A Quiet Passion, The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), Prevenge, Moonlight, Manchester by the Sea, Chemi Bednieri Ojakhi (My Happy Family).

Older Films Watched in 2017:

Up the Junction (1965), The End of Arthur’s Marriage (1965), In Two Minds (1967), (500) Days of Summer (2009), Bananas (1971), Cathy Come Home (1966), The Rank and File (1971), 3 Clear Sundays (1965), The Big Flame (1969), Poor Cow (1967), Kes (1969), The Gamekeeper (1980), Riff-Raff (1991), Raining Stones (1993), Midnight in Paris (2011), Blackjack (1979), Looks and Smiles (1981), Family Life (1971), Fatherland (1986), Hidden Agenda (1990), Ladybird Ladybird (1994), McLibel (Extended Edition) (2005), Land and Freedom (1995), Carla’s Song (1996), My Name Is Joe (1998), Bread and Roses (2000), The Navigators (2001), Sweet Sixteen (2002), Ae Fond Kiss (2004), The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006), Route Irish (2010), The Angel’s Share (2012), Jimmy’s Hall (2014), The Spirit of ’45 (2013), It’s a Free World… (2007), I, Daniel Blake (2016), Raghs Dar Ghobar (Dancing in the Dust) (2003), Shar-Re Ziba (Beautiful City) (2004), Chaharshanbe-Soori (Fireworks Wednesday) (2006), Trainspotting (1996), About Elly (2009), A Separation (2011), Looking For Eric (2009), Captain America: Civil War (2016), Border Radio (1987), Gas Food Lodging (1992), Mi Vida Loca (My Crazy Life) (1993), Grace of My Heart (1996), Four Rooms (1995), Things Behind the Sun (2001), Mystery Girl (A Crush On You) (2011), X-Men: Apocalypse (2016), Beaches (1988), The Cabin in the Woods (2011), Ring of Fire (2013), Pitch Perfect 2 (2015), Dog Soldiers (2002), The Descent (2005), Doomsday (2008), Centurion (2010), Moana (2016), Speed Racer (2008), Good Night and Good Luck (2005), Hollywood Boulevard (1976), Piranha (1978), Rock’n’Roll High School (1979), For the Love of Spock (2016), The Howling (1981), Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983), Explorers (1985), Innerspace (1987), Gremlins (1984), The ’Burbs (1989), Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990) Matinee (1993), The Second Civil War (1997), Small Soldiers (1998), Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003), Finding Dory (2016), Burying the Ex (2014), The Warlord: Battle For the Galaxy (The Osiris Chronicles) (1998), The Hole (2011), Zootopia (2016), Army of Darkness (1992), Madagascar (2005), Patrick (1978), Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005), Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007), Long Weekend (1978), Harlequin (1980), Road Games (1981), Keanu (2016), Razorback (1984), Suicide Squad (2016), Snapshot (One More Minute) (1979), Treasure of the Yankee Zephyr (1981), Fortress (1985), Link (1986) Frog Dreaming (The Quest) (1986), Windrider (1986), Visitors (2003), Storm Warning (2007), Long Weekend (2008), Nine Miles Down (2009), Not Quite Hollywood (2008), Strangers With Candy (2005), Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992), Rushmore (1998), Bottle Rocket (1996), Moulin Rouge! (2001), The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), Steve Jobs (2015), Fantastic Mr Fox (2009), The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), Moonrise Kingdom (2012), Erin Brockovich (2000), The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), Traffic (2000), The Darjeeling Limited (2007), Mad Max (1979), Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981), Grosse Pointe Blank (1997), Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome (1985), Happy Feet (2006), The Witches of Eastwick (1987), Babe (1995), Babe: Pig in the City (1998), Happy Feet Two (2011), Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), Lorenzo’s Oil (1992), Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966), Doctor Strange (2016), Paradise Alley (1978), The Package (1989), Rocky (1976), Rocky II (1979), Rocky III (1982), Rocky IV (1985), Rocky V (1990), Rocky Balboa (2006), First Blood (1981), Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985), Rambo III (1988), Rambo (2008), Saturday Night Fever (1977), Stayin’ Alive (1983), The Expendables (2010), The Expendables 2 (2012), The Expendables 3 (2014), The Party at Kitty and Stud’s (Italian Stallion) (1970), No Place To Hide (Rebel) (1970), Kingsman: The Secret Service (2014), Blade Runner (The Director’s Cut) (1982), Delicatessen (1991), The City of Lost Children (1995), Dante 01 (2008), Micmacs (2009), Amelie (2001), The Young and Prodigious TS Spivet (2013), A Very Long Engagement (2004), Knife in the Water (1962), Cul-De-Sac (1966), Repulsion (1965), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Macbeth (1971), What? (1972), Chinatown (1974), The Tenant (1976), The Night of the Generals (1967), Tess (1979), Pirates (1986), Frantic (1988), Bitter Moon (1992), Death and the Maiden (1994), The Ninth Gate (1999), The Pianist (2002), Oliver Twist (2005), The Ghost Writer (2010), Weekend of a Champion (1972), Carnage (2011), The Fearless Vampire Killers (Dance of the Vampires) (1967), Venus In Fur (2013), Roman Polanski: A Film Memoir (2011), Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired (2008), Roman Polanski: Odd Man Out (2012), L’enfance nue (Naked Childhood) (1968), Nous ne vieillirons pas ensemble (We Won’t Grow Old Together) (1972), La gueule ouverte (The Mouth Agape) (1974), Passe ton bac d’abord (Graduate First) (1979), Loulou (1980), À nos amours (To Our Loves) (1983), Police (1985), Sous le soleil de satan (Under the Sun of Satan) (1987), Van Gogh (1991), La maison des bois (The House in the Woods) (1971), The Room (2003), Le garçu (1995), Star Wars – Episode VII: The Force Awakens (2015), Bushfire Moon (Miracle Down Under) (1987), The Handmaiden (2016), Elf (2003), It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Scrooged (1988), Duck Soup (1933).

Short Films Watched in 2017:

A Question of Leadership (1981), Which Side Are You On? (1985), A Million Miles Away (2014), Mitch & Judy (WIP) (2017). Combat (1999), Bottle Rocket (1994), Candy L’eau (2013), Castello Cavalcanti (2013), Come Together (2016), The Bad Guy (2017), Red (2017), 40 000 Years of Dreaming (1997), Can You Dig It? (WIP) (2017), 2036: Nexus Dawn (2017), 2048: Nowhere To Run (2017), Blade Runner Black Out 2022 (2017), The Bunker of the Last Gunshots (1981), La manege (1981), No Rest For Billy Brakko (1984), Things I Like, Things I Don’t (1989), Detour (2017), Rude Raid (1985), Maitre Cube (1985), Etc (1988), Le defile (1986), Le Topologue (1988), Le Circe Conférence (1989), Dynamo (????), KO Kid (1994), Les Cyclopodes (1995), LS Dead (1996), Touentiouane (1998), Exercise of Steel (1998), Samadhi (2005), Casanova (2015), Teeth Smile (1957), Break Up the Dance (1957), Murder (1957), Two Men and a Wardrobe (1958), Lampa (1959), When Angels Fall (1959), The Fat and the Lean (1961), Ssaki (1962), Greed (2009), A Therapy (2012), Isabelle aux dombes (1951), Congrès eucharistique diocésain (1953), Drôles de bobines (1957), L’ombre familière (1958), L’amour existe (1960), Janine (1962), Maître galip (1964), Byzance (1964), Pehlivan (1964), Istanbul (1964), La corne d’or (1964), Bosphore (1964), Van Gogh (1965), La Camargue (1966), Liz Drives (2017), AD/BC: A Rock Opera (2004).