“That’s the other thing you learn in grief,” Rory Kinnear told The Observer in 2023, “and maybe this is why I’m not scared of it, is the relationship continues.”

I’ve ready more than a few interviews in which actor Rory Kinnear talks about the dimensions of grief, something he does thoughtfully and articulately. And, when the situation calls for it, angrily. (Read his beautiful tribute to older sister Karina in The Guardian and get apoplectic at Britain’s Tories all over again.) The subject comes up a lot when he’s speaking to the press, because when he was very young Rory lost his father, actor Roy Kinnear.

You know Roy, even if you think you don’t. He was Veruca Salt’s father in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, a man of industry under the thumb of a bossy twelve-year-old, convinced everything he sees has a price, unsure of whether to treat Wonka as a co-conspirator, rube, or enemy. It’s probably the only performance in the film that pulls your eyes from Gene Wilder; Henry Salt’s ruddy and changeable features simultaneously betraying cynicism, credulousness, confusion, wonder, fear at the world he’s found himself in.

That’s just one of what IMDb says is 173 credited screen roles; roles that include the Cheshire Cat in one of the better Alice In Wonderland adaptations, a small but memorable part in the Beatles film Help!, the Plastic Mac Man in the brilliant postapocalyptic surrealist comedy The Bed-Sitting Room, the gladiator instructor in the big screen version of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, and (personal favourite) the flustered Nazi guard in the Ripping Yarns episode Escape From Stalag Luft 112B. Roy Kinnear was a proper fixture of British film and television, and I don’t think there’s anyone else who occupied the same space he did, somehow able to represent both the upper and working classes, the oppressor and the downtrodden, all at once.

On the day I’m writing this, there are news reports announcing the death of Richard Chamberlain, who has passed two days before his 91st birthday. It’s a respectable innings, and one that should also have been enjoyed by his Return of the Musketeers co-star Roy, who died during the making of that movie while filming a stunt, at the horrifically young age of 54.

He left behind a young family, including ten-year-old Rory. You likely know grown-up Rory from these roles:

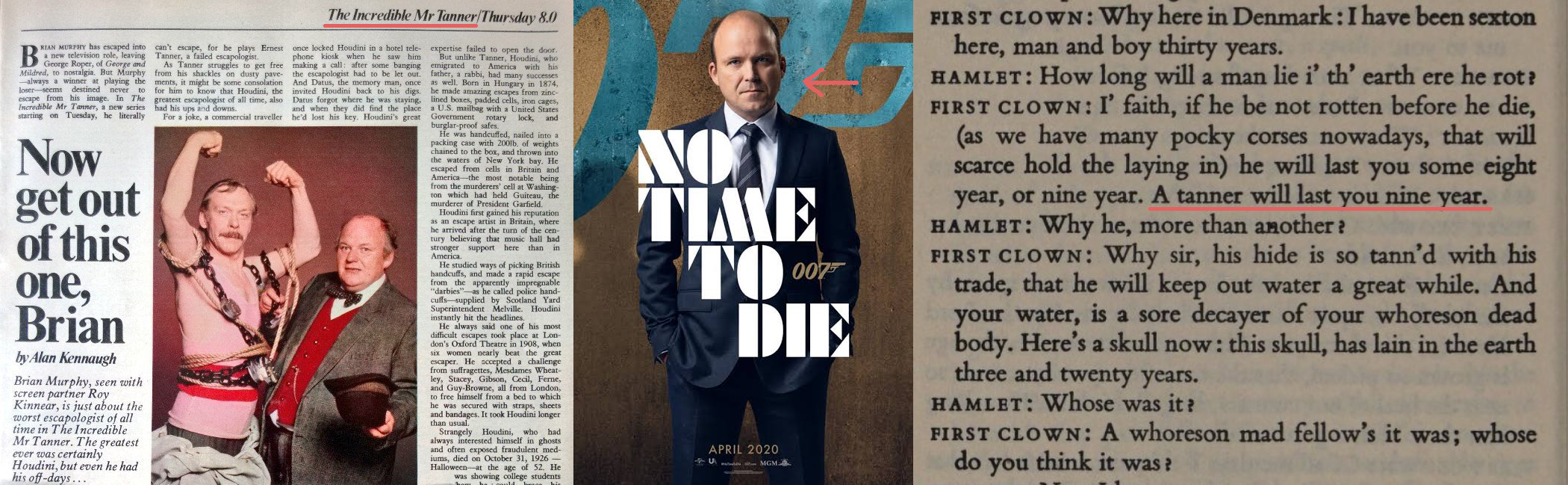

“One of the few benefits of the continued Tory governments,” he said in 2023, “is that people continue to look to me to play Tory ministers.” His bureaucratic visage may have landed him the MI6 Chief of Staff role in the James Bond films, and the Prime Minister in what is still the most memorable Black Mirror episode, and another Prime Minister in the relentlessly-addictive The Diplomat, but if you’ve seen his other work (Alex Garland’s Men, National Theatre Live’s The Last of the Haussmans), you probably know his range far exceeds buttoned-down establishment figures. (Look, if you’re not in the mood for a hagiography, skip to the end. I’m just warming up.)

I first took proper notice of him when I saw him in the 2010 National Theatre Live production of Hamlet. Hamlet is probably – unimaginatively – my favourite play, but I recall being reluctant to go. I’d seen so many productions at that point, I was convinced nobody had anything new to tell me about the role, a pretty conceited idea that was immediately proven wrong. Rory’s performance was the best I’d seen, revealing shades of the character I’d never considered, and investing a new vitality into lines so familiar, their original meaning had been obscured what was now a trope. And yet, when Rory says “Alas poor Yorrick”, you’d swear the thought had occurred to him in the moment.

It reminded me of what my own father told me about the moment Shakespeare truly opened up to him: watching Sir Michael Hordern as Lord Capulet in the BBC’s 1978 production of Romeo and Juliet, uttering each line as if it was a passing thought, the strict rhythms of iambic pentameter no obstacle to the patterns of normal speech.

I’ve not seen that particular production, but the anecdote was front of mind when I recently discovered the 1964 BBC production of Hamlet – only the second to be filmed in Denmark’s actual Elsinore! – with a cast featuring Christopher Plummer, Michael Caine, Donald Sutherland, Robert Shaw…

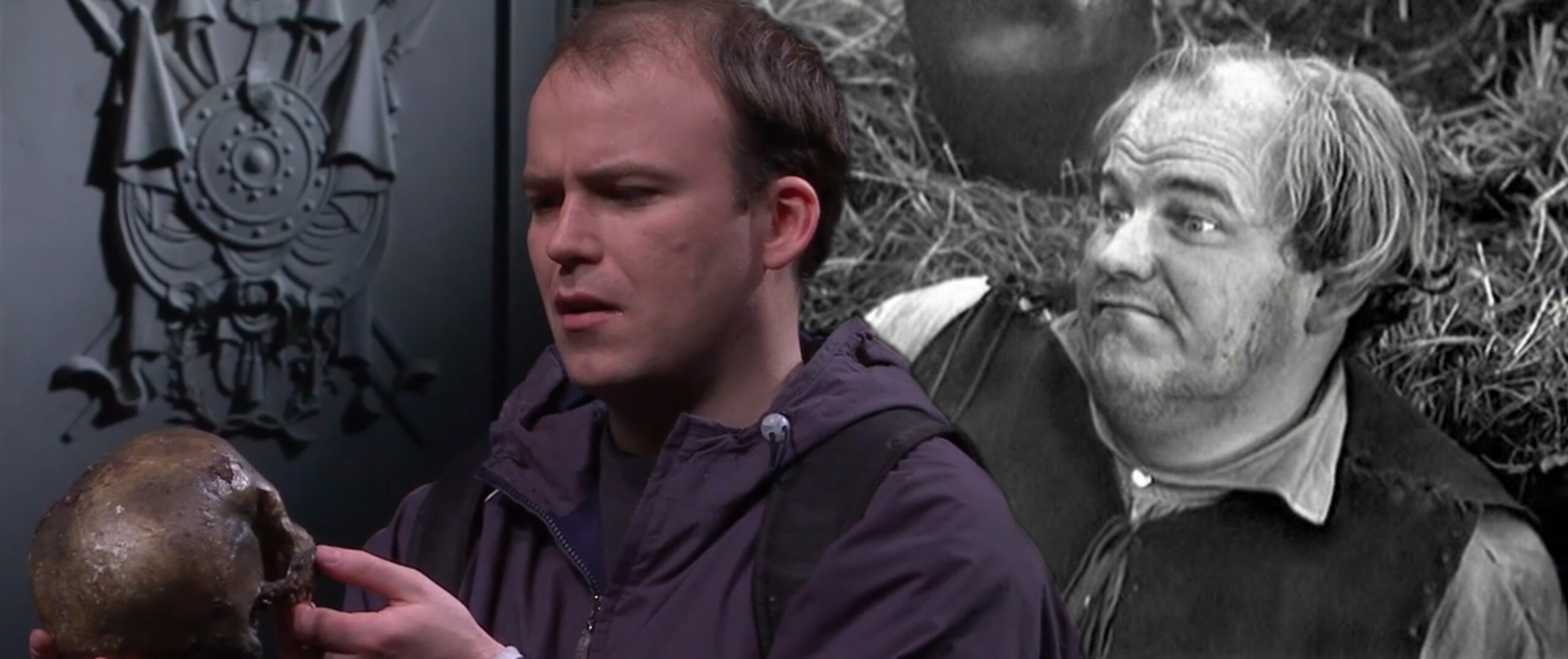

…and also, in one scene, laying waste to the ornate treatment of the material, is Roy Kinnear as the Gravedigger. He too speaking as if it’s all off the top of his head, no stilted delivery to be heard. It was instantly my favourite performance of the part, ever. With respect to all Gravediggers past and future, has anyone done so much with so little, treating these lines as the tips of an iceberg, hinting at a long and storied relationship between his character and the now-skeletal Yorrick? His joyful memory as potent as Hamlet’s melancholy?

You’ve probably guessed at where this is all going. And also wondered why it’s taken so many words to get there. But stick with me, because like the Mad Prince in Act II, scene two, I have at least a couple more.

As soon as the idea hit, I couldn’t shake it: would it be possible to mesh the two performances together in a crafty edit? See Rory’s Hamlet play opposite Roy’s Gravedigger, father and son playing in what might be the best scene in the greatest play of all time? A scene that captures the complexities of grief in a way that the vengeance-spurring mourning for Ophelia or the King does not?

Honestly, I hesitated. Mostly, I was wary of the propriety of it all. It’s a pretty presumptuous thing to do, folding bits of time together that perhaps shouldn’t touch, forcing a meeting of 30-year-old Roy and 32-year-old Rory, contaminating someone’s actual life with a high-concept bit of performance art. Do interviews like this make it okay, or am I just living out a parasocial relationship but it seems classy because it’s Shakespeare? Are the Kinnears my Kardashians?

In the end, I decided to stop overthinking it. Which is a sentence I’m sure you enjoyed given you’re about a thousand words and counting into this essay, but you get my meaning. Such a video doesn’t need to be anything more than a curio: it’s simply the performers and their performances being remixed, no part of them used but that which they already gave to the world. Maybe I allowed one poignant juxtaposition in the edit, but there’s no saying I wouldn’t have done similar if I were mixing, say, Christopher Plummer’s Hamlet and David Calder’s Gravedigger. (Which, now I say it, I’m almost tempted to do, just to see how it compares. Maybe another time.)

In the end, I decided to stop overthinking it. Which is a sentence I’m sure you enjoyed given you’re about a thousand words and counting into this essay, but you get my meaning. Such a video doesn’t need to be anything more than a curio: it’s simply the performers and their performances being remixed, no part of them used but that which they already gave to the world. Maybe I allowed one poignant juxtaposition in the edit, but there’s no saying I wouldn’t have done similar if I were mixing, say, Christopher Plummer’s Hamlet and David Calder’s Gravedigger. (Which, now I say it, I’m almost tempted to do, just to see how it compares. Maybe another time.)

I can even play up the triviality with some pop culture gymnastics: Rory (best known as James Bond’s Bill Tanner) and Roy (who starred in the short-lived 1981 sitcom The Incredible Mr Tanner), play a scene in which they discuss how long a professional tanner will last in a grave before he decomposes. There you go. Trivial and proper.

Or maybe it doesn’t need to be anything more than me remixing my favourite Hamlet with my favourite Gravedigger, and the identities of the actors are irrelevant. Choose the motivation that best suits.

Either way, here it is. Kinnear Hamlet, starring Rory as Hamlet and Roy as the Gravedigger.

(Notes: forgive the digital artefacting, I was slightly limited by disparate formats of the source material; also, for the sake of editing necessity, 1964 Hamlet Christopher Plummer and 2010 Gravedigger David Calder both deliver a single word. Appropriately, those words are “how” and “why”. More respectable triviality.)

Click here to find times and locations for National Theatre Live screenings and then go see them. It doesn’t really matter what the show is. They have an unbroken hit rate, as well as a reputation for being extremely tolerant of anyone who bends copyright law for the purposes of making something interesting.

Hamlet At Elsinore (1964) was released as a region one DVD in the US alone, and seems to be only available via third-party sellers. We’ll have a conversation about the inaccessibility of art another time.